Wakeboarding Like its snowy counterpart, wakeboarding—which came to prominence in the late 1970s—is a relative newcomer to the extreme sports scene. In addition to the obvious traits of riding a shaped plank over H2O in either its solid or liquid state, snowboarding and wakeboarding share other, more subtle similarities. With the exception of body lean, wakeboarding's stance is similar to that of snowboarding. Photo 1 shows a typical wakeboarder's backward-leaning posture, which helps maintain balance on the water, while resisting the pull of the boat. His arms extend in the direction of travel, and his hands maintain a comfortable grip on the tow line while the upper body is slightly twisted to distribute the pull load on the arms. But compare the wakeboarder's stance overall with that of the snowboarder in photo 2; notice the placement of each rider's feet on the board and the way their hips align with the direction of travel. Incidentally, the backward lean shown in photo 1 does not typically pose a problem to experienced wakeboarders who are learning to snowboard. In fact, the ability to ride switch on a wakeboard provides plenty of opportunities to practice adjusting body lean. However, many wakeboarders trying out snowboarding may carry over the upper body twist used to hold the tow rope. Instructors will have to work with these students to attain the proper basic snowboard stance shown in photo 2.

Photo 1________________________________________Photo 2

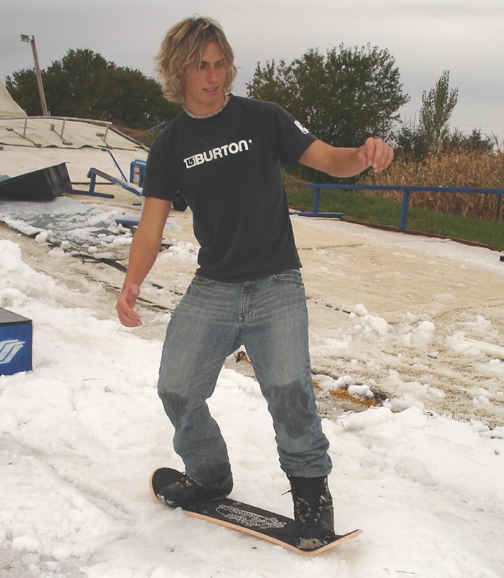

Photo 3________________________________________Photo 4

More resemblances between the two sports are evident in rail maneuvers. The wakeboarder in photo 5 has ridden up the entry ramp and hopped into a boardslide position, on a slider (wakeboard rail). The snowboarder in photo 6 has glided from the take-off ramp onto the rail in classic boardslide form. The skill sets between the two are virtually identical (although, speaking from experience, crashes on the wakeboard slider are less painful than those on a terrain park rail). Because the wakeboarder accelerates up the ramp, thus leaving a little slack rope while performing the maneuver on the rail, the otherwise necessary backward lean is negated. The take off (ATML model) or hop onto a rail is an important part of a snowboard trick. Likewise a good take off or hop onto a slider (wake board rail) helps retain terrain park skills during the summer. The approach to a wake board slider requires a good eye for lining up, a. skill retained throughout the summer, so that you are ready for your first winter run through the park.

Photo 5________________________________________Photo 6

Jumping techniques are also similar. In photo 5, the wakeboarder has approached the jump straight, ridden up the ramp, and pulled up his feet for flight stability. The snowboarder in photo 6 has followed the same pattern. Many grabs and other tricks are analogous, if slightly limited in wakeboarding due to the necessity of keeping one hand on the tow rope.

Photo 7________________________________________Photo 8

The resemblances continue in the butter slide shown in photos 7 and 8 In addition to the similarity between how the wakeboarder performs the trick (photo 7) and how it is executed by a snowboarder (photo 8), notice the likeness between the hourglass-shaped wakeboard and a snowboard.

Photo 9________________________________________Photo 10

For added challenge, try a wake skate, a small wakeboard without bindings (photo 9) that compares with the snow skate (Photo 10), a binding-less snowboard that closely resembles a skateboard deck. Snow skates have been used at small jib parks and are a favorite with skate boarders because of the similarity in executing various tricks. Wake skating develops surface trick skills as opposed to big air skills that necessitate bindings to successfully complete. The proper stance for both boards is similar, as are the maneuvers used to ride them without the benefit of bindings. The key is to maintain contact between the feet and the board when performing moves such as an ollie, which helps bounce the board up toward the body. Some tricks, however, like kick flips, require the rider to leave the board momentarily then re-establish contact.

Photo 11

Like their snow-specific siblings, wakeboards come in different styles for varying types of use. The middle wakeboard in photo 11, for example, is a conventional board with laced bindings. There are fins at each end of the board that provide stability whether riding regular or switch. The board at the right is a bindings-free wake skate, and the board on the left features a rounded, hourglass shape that is best for surface tricks and spins. If you don’t have a boat, JetSki, or other suitable watercraft—and a buddy to drive it— there are a number of groups and clubs that offer the opportunity to both learn and excel at wakeboarding. So if you’re searching for an off-season opportunity to improve balance, keep those snowboarding muscles in shape, and hone movement-related skills, why not give wakeboarding a try? Even though you’ll be spending a lot of time in the water, you’ll emerge from the long, hot summer a little less rusty than if you followed your normal routine of watching snowboard videos and praying for early snow.

Chuck Roberts teaches snowboarding and skiing at Wisconsin’s Wilmot Mountain. As an AASI Level II instructor, he’s been teaching snowboarding since 1987. Also a PSIA Level III alpine ski instructor, he’s been teaching skiing since 1970. He works as a consulting engineer.

BACK TO ROBERTS SKI AND SNOWBOARD INSTRUCTION HOME PAGE

BACK TO ROBERTS SKI AND SNOWBOARD INSTRUCTION HOME PAGE