Spring has arrived, and with it the extended daylight, tepid temperatures, and melting snow that direct our attention to activities requiring fewer layers of clothing. But this doesn't mean we have to stop skiing—nor does it mean we have to journey to remote alpine regions to do so. Water skiing shares many similar thrills and skills with its cold-weather counterpart, and many snow skiers trade the chairlift for a tow rope in the summer months as a way to have fun while retaining muscle mass and refining their winter skiing abilities. It's probably not mere coincidence that Warren Witherall, one of the early pioneers of American ski instruction, was also a champion water skier. Water skis made their debut in the early 1920s, and water skiing became a popular exhibition sport nationwide by the 1930s. Like its snow-based sibling, water skiing has since spawned several disciplines, including slalom skiing, trick skiing, ski jumping, show skiing, and barefoot skiing.

TWO-SKI BASICS

The type of water skiing closest to snow skiing is two-ski water skiing as shown in photo 1a. Notice the water skier's stance; the feet are slightly apart and the skier's upper torso is facing in the direction of travel, similar to the snow skier in photo 1b.

Photo 1A________________________________________Photo 1B

Since the water skier must hold a tow rope and is being pulled by a boat, there is a moderate backward lean, which is necessary to offset the pull of the boat along with the planing drag of the ski and is the primary difference between a snow skiing and water skiing stance. Incidentally, over the years I have taught a number of water skiers new to snow skiing and have observed that water skiers are often quick to pick up on steering and balancing, but have a tendency to sit back—a habit from leaning back to resist the pull of watercraft. It should be noted that the water skier stance is nearly perpendicular to the water ski as the snow skier is perpendicular to the snow ski. The apparent leaning back of the body comes from the water ski planing on the water in the tip up mode, a physically necessary, balanced stance to support the skier’s weight. The apparent backward lean with respect to the water surface is a function of speed and type of ski and is found in water skiers of all abilities. Water skiing turns are made by tipping the body and steering the feet in the direction of the turn, similar to modern shaped ski turning techniques. In general, water skiing requires a minimum speed of about 16 mph to maintain stability and make smooth turns on wide skis, and about 25 mph for the conventional combo skis shown in photo 1a.

SLALOM SKIING

Most water skiers eventually make the transition from two skis to a single ski, which is called slalom skiing. Photo 2a shows a slalom skier with one foot in front of the other, a divergence from the feet-together position demonstrated by the snow skier in photo 2b. While it is common to slalom ski with the less-dominant foot forward, an individual's preference is often determined through trial in error.

Photo 2A________________________________________Photo 2B

Photo 2AB

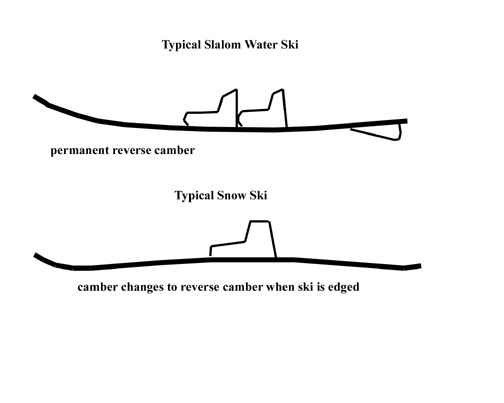

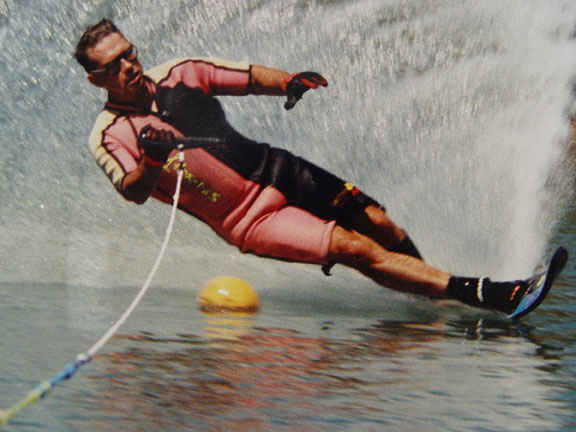

Photo 2ab One of the most noticeable visual characteristics of the slalom water ski is that it must be slightly angled upward to provide hydrodynamic lift. There should be a balance between keeping the tip out of the water and allowing the ski’s base to plane on the water’s surface. This makes the slalom water skier appear to lean back dramatically, although the water skier is actually perpendicular to the ski, much like the snow skier is perpendicular to the ski. Waterskiing can be compared more closely to skiing powder (Photo 2ab) since the snow skis are planing on fluffy light snow providing lift like a water ski. Notice that the powder snow skier is leaning slightly back compared to the snow surface but is perpendicular to the skis. Both snow and water skiing have characteristic stances, but participants well versed in one discipline tend to easily adjust to a balanced stance in the other. Turns on a slalom ski are made by tipping the body to the right or left; there is little knee angulation involved. As soon as a slalom skier leans, he or she begins to carve thanks to the built-in reverse camber of slalom skis (jump and trick water skis also have this feature). Photo 2bc compares the shape of a water ski and snow ski. The water ski has a nearly permanent reverse camber shape and is much stiffer than the snow ski. The snow ski has camber and forms a reverse camber shape like the water ski when edged on the snow. The rear portion of the water ski is flatter than the fore body for cutting in a nearly linear fashion through the wake to the next buoy. The more curved fore body of the water ski is used for carving in the water to make the slalom turn. A slalom skier will shift the weight back for cutting through the wake and shift more forward to complete a turn around the slalom buoy. (It should be noted that some snow ski manufacturers are also coming out with permanently reverse cambered skis for powder skiing.) Photo 2bc

Photo 2BC

Photo 2c___________________Photo 2D__________________Photo 2E

The skier running a slalom course in photo 2c is making a turn at a buoy, the water-bound equivalent of a slalom gate on a downhill course. Water skiing slalom turns require more extreme tipping — also known as inclination — in order to engage the permanent reverse-cambered edge of the ski. One snowsports analogy to this would be riding a mono-ski or a carving board as shown in photo 2d. The rider on the carving board and the skier in photo 2e put more pressure on the edge, causing more reverse camber for a crisp turn. Knee and hip angulation are utilized to a higher degree in the snow sports when compared to water skiing. A slight difference between turning on water skis versus turning on snow skis emanates from the nature of the skis themselves. Water skis bend very little, while snow skis offer more flex. The water ski has a fixed curvature, while the snow ski has a flexible curvature governed by the edge angle of the ski with the snow. When turning, the water skier must move his or her center of mass forward and to the inside of the turn to engage the more curved front of the slalom ski (photo 2bc) in order to make a tighter turn. These movements of the center of mass forward and to the inside are similar in both snow and water skiing, however waterskiing generally uses a more pronounced lateral movement. Although making a turn on water skis presents a slight variance from turning on alpine skis, the two do share similar knee and ankle flexion, which in water skiing are used to absorb the "bumps" of crossing wakes at high speeds and to adjust the body position.

SKI JUMPING

While there are minor body position variances in turning on water skis versus snow skis, ski jumping on snow and water are almost identical. As a matter of fact, the flying form with divergent ski tips shown in photos 3a and 3b originated with water skiing and was adopted by snow ski jumpers. That's not to say that there aren't subtle differences; the flight of the snow ski jumper features more forward lean because the landing slope is pitched downward as opposed to that of the water ski jumper, whose landing surface is level.

Photo 3A____________________________Photo 3B(courtesy Norge Ski Club)

Photo 3C (courtesy of USA Water Ski)

Still, the aerodynamic body positions of both skiers remain identical with the exception of the water ski jumper discreetly holding the tow rope handle near the hip. Aerodynamic lift, a key ingredient for a long jump, is accomplished with body position and the use of wider, flat jump skis that act like aircraft wings. The primary difference between water and snow ski jumping is in the approach to the jump itself. A snow ski jumper approaches the jump straight-on. A water ski jumper will cut to one side of the jump ramp, then cut back to increase his or her speed while going over the jump. Because the boat pulling the water skier has to pass the ramp, the skier approaches the jump at an angle but straightens after getting on the ramp and prior to "take-off." Photo 3c shows a water ski jumper cutting or carving to the jump with a body position quite similar to the snow skier in photo 2e.

FREESTYLE

Freestyle snow skiing in the terrain park is growing in popularity and many instructors are teaching and coaching students in jumping and rotary related moves. Trick water skiing is a good way to retain and even develop these skills since crashes in the water are less severe than on the snow. Figure 4a shows a trick skier performing a simple 180 degree wake jump. This is a move that hones rotary and balance skills that can be used for spins on a feature (Photo 4b), basic 180 & 360 degree jumps or elementary freestyle moves such as surface flat spins.

Photo 4A____________________________________________Photo 4B

Photo 4c___________________Photo 4D__________________Photo 4E

Competition trick skiing involves performing as many unique AWSA (American Water Ski Association) approved tricks as possible in two 20 second passes. The AWSA rule book covers numerous tricks ranging from spins to flips. Trick skiing is further broken down into two forms: toe trick skiing, where the tow rope handle is attached to the foot; and conventional hand grip trick skiing. In Photo 4c the trick skier is performing a toe front, while Photo 4d is the toe back, each move racking up 100 points in competition. This type of waterskiing perfects balance and rotary skills. The one-ski ballet skiing maneuver shown in Photo 4e might be considered to be the counterpart to toe trick skiing.

EQUIPMENT

Like snow skis, water skis come in a variety of shapes and sizes for different uses. The ski in the top of photo 5 is from a pair of jump skis, which are the longest tournament skis—usually more than 80 inches (racing water skis are typically longer). Jump skis are also wide with a shallow fin, which allows the skis to slide up a ramp without marring the surface, yet still have enough depth to help the skier work with the hydrodynamics involved in landing long jumps.

Photo 5

UPPER-BODY WORKOUT

When water skiing in a straight line, the pull generated against the tow rope can be on the order of 40 to 80 pounds. Between 400 and 500 pounds of pull can be generated for a split second while cutting in a slalom course. Consequently, water skiing provides a solid upper-body workout that snow skiing doesn't offer—unless you really like rope tows. Skiing on water also requires sustained energy and muscle use. An hour of slalom course water skiing or trick skiing can be as tiring as a full day of snow skiing. It takes about 5-10 hp to propel a water skier traveling in a straight line at 25 mph because of water friction, planing drag and wind related drag. The skier’s legs must support the skier’s weight, the component of force from the tow rope and additional forces from sharp turns in a slalom course. The arms and shoulders get a similar workout, since they are the means of transferring the propulsion force (tow rope force) to the body. In snow skiing, snow friction is relatively low and gravity does the work, so energy is expended in flexing, extending and edging but to a much lesser degree than water skiing.

RIDE THE WAVES

Water skiing, of course, requires some type of suitable watercraft—and driver—to pull the skier. If you don't have access to a boat or personal watercraft (Jet Ski, Wave Runner, etc.), joining a water skiing club is an economical solution. There are a number of groups across the country that offer an opportunity to learn and excel at water skiing. In addition to recreational waterskiing, competition tournaments that are divided into age group ranges from 4 to 90 are hosted by AWSA clubs, so skiers of all ages have a chance to win an event. For more information on how to get hooked on water skiing go to www.usawaterski.org which has a extensive list of water ski clubs and water ski sites. Both beneficial and a blast, water skiing is a great summer pastime for those who just can't part with their planks when the snow vanishes. And to alpine skiers reluctant to test their skills on liquid, think about this: if you're a snow skier, you're just one state of matter away from being a water skier.

Chuck Roberts has taught alpine skiing since 1970 and snowboarding since 1987. He is a PSIA-certified Level III alpine and AASI-certified Level II snowboard instructor at Wisconsin's Wilmot Mountain. He has been waterskiing for over 48 years and competes annually in AWSA tournaments.

BACK TO ROBERTS SKI AND SNOWBOARD INSTRUCTION HOME PAGE

BACK TO ROBERTS SKI AND SNOWBOARD INSTRUCTION HOME PAGE