By

Chuck Roberts and John Roberts

Terrain parks are a

big deal at most snow sports areas because of demands by snowboarders and

skiers to experience a variety of features during their visit to your area. If

you are teaching freestyle in terrain parks, you may be approached periodically

by the area management to advise on terrain park

feature design and how to make a park interesting to riders. Although many

large resorts have terrain park designers on staff, many areas do not and often

rely on the snowboard staff for input. After all, you are a skilled rider, you

use the park and you teach students how to use the park, ergo you are an

excellent in-house consultant. Panicked? Don’t be. The following is a primmer

on the ins and outs of terrain park features, maintenance, management and park

layout.

Rails

Rails have their root

in skateboarding where skate boarders would ride and grind on a rail similar to

a handrail on stairs. Early snowboarders used fallen or bent over trees as

natural rails. As terrain parks developed, manufactured rails became

predominate in several sizes, shapes and cross-sections.

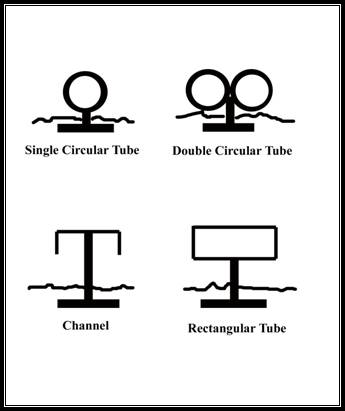

Figure

1

Figure 1 illustrates

the variety of rail cross-sections. The single tube rail appeared early on and

was often made of a ductile steel or plastic pipe ranging from 3 to 6 inches in

diameter. This rail is tough to ride since there are no flat areas to stabilize

the board. The double barrel tube rail

was also available and allowed for easier riding since it was flatter, and a

snowboard was less likely to tip. By

far, the most popular rail is the rectangular steel tube design: usually a 2”

by 4” or 2” x 6”tube. Sometimes, as a substitute, the steel channel rail is

found, which tends to be identical on the upper surfaces but has a different

support structure. Figure 2A shows a classic, advanced, 2”x 6” steel straight

rail with gap-on ramp. Figure 2B shows another classic design where the tubing

at the entry and exit is bent down. This design is easier for your beginning park

riders, as the feature requires a less precise takeoff and dismount.

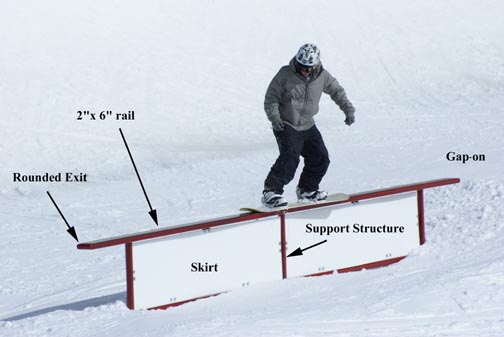

Figure

2A

Figure

2B

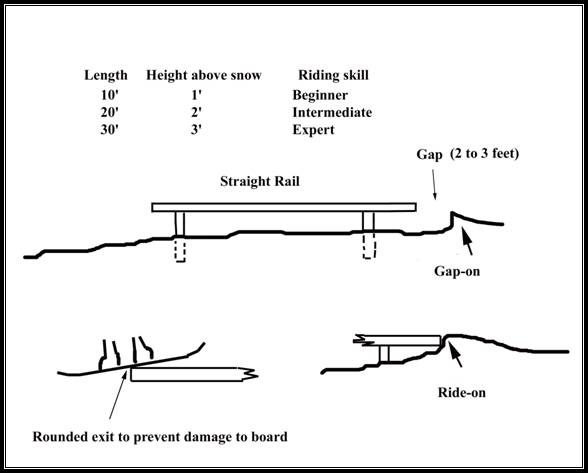

Figure

3

Figure 3 shows some

of the ins and outs of terrain park rails. Ramps can be either gap-on or ride-on.

The ride-on ramps are easier for your timid beginning park riders, but once

they get the hang of grinding, then the gap-on is preferred. Eye the arc of the

gap-on ramp to make sure your students, traveling at moderate speeds, can take

off and land on the rail without difficulty. A worn down ramp may not give

enough lift for your students, necessitating moving on to another feature and

notifying management. Most rails have a beveled (rounded) exit and entry to

reduce the chance of damage to the bottom of the snowboard, especially for

riders mounting the rail slowly and who do not ollie off the end (Figure 2B and Figure 3). In the past, some riders have also beveled the

edge of their snowboards to facilitate board slides and reduce the chance of

engaging an edge on the feature. Some boards are also designed with beveled

edges for grinding on various terrain park features. Rail features may need

periodic grinding of burs that form during usage. Some riders will mount a rail on edge, which

can cause a bur in the steel that may affect the riding of others. Burs not

only damage the running surface of the snowboard but can cause additional drag.

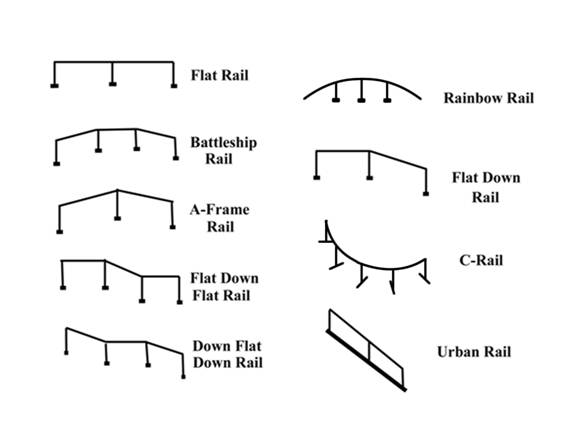

Figure 4 is a

sampling of the variety of rails found in many terrain parks. Most rails should

be installed with the long axis down the fall line to preclude the tendency to

slide off one side or the other that can occur on rails that are not placed

along the fall line.

Figure

4

Boxes

Boxes are fun features

for both beginning park riders and experts. Figure 5 shows typical construction

of a flat box which includes a top sheet, coping and the basic box structure.

The top sheet is usually a wear resistant polymer (plastic) such as nylon or

polyvinylchloride and is secured to the box structure. The coping acts a wear

resistant corner, usually constructed of steel. The skirt can be plywood or

plastic sheet as it usually covers the box structure and internal parts. Boxes

are usually pretty stable features, but under certain conditions the sun can

shine on one side and melt the snow on that side, causing the box to tilt. It is

helpful to check out the features prior to your lesson, since one that is not

level may add to teaching difficulties, especially for your beginning park

riders. As always, report to management

any deficiencies you find. Another way to tell if a feature is not down the

fall line, or is tilted, is by looking at the landing area. If the landing area

is not along the long axis of a straight feature, then there is a possibility

that it is either tilted or not down the fall line.

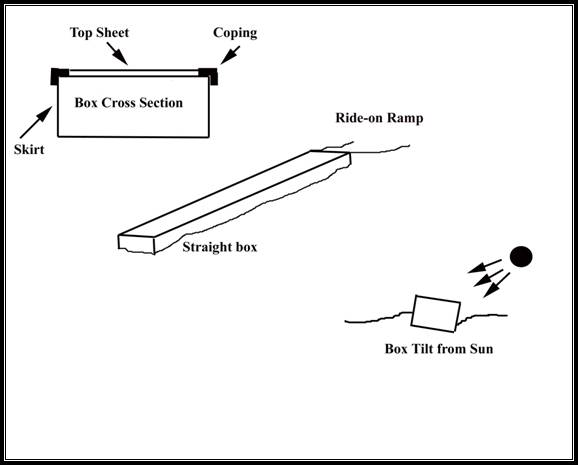

Figure

5

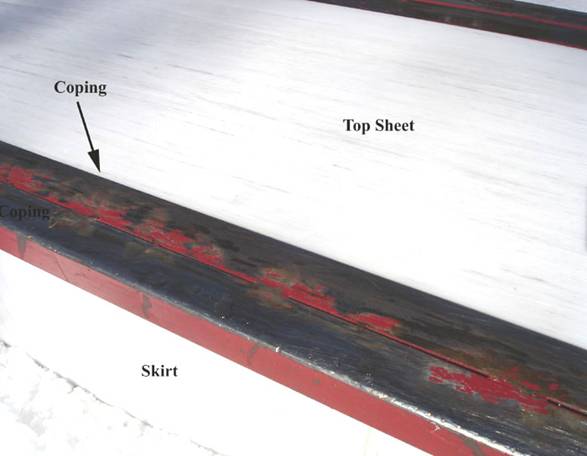

Figure

6

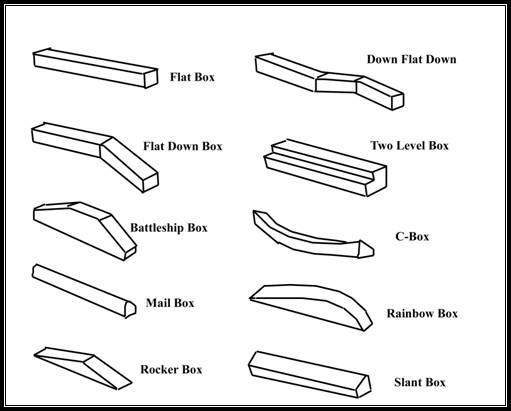

Figure 6 is a

close-up view of a typical box, showing steel coping and white polymer top

sheet. Notice the nicks on the steel coping from riders, which is a normal

result of usage. Figure 7 is a sample of typical boxes found in many terrain

parks. The use of boxes in your terrain park lesson plan gives you great

flexibility in your teaching, since both your beginning and advanced park

riders can try out new moves on a forgiving feature. From our experience, it is

not unusual that some in the class may be working on crooked grinds, while

others are performing 720’s on a box.

Figure

7

Figure

8

Figure 8 shows a

relatively new feature that resembles a picnic table, which has a base

structure similar to that of a rail, but a riding surface that mimics a box. The

advantage of this newer design is they are easier to manufacture and easier to

move around. On the flip side, they may become wobbly after repeated usage,

depending on how the support structure is planted in the snow. “Picnic tables”

can be manufactured wider than normal boxes, which is

a big plus for your beginning park riders, as it is more forgiving of an

imprecise line up with the feature.

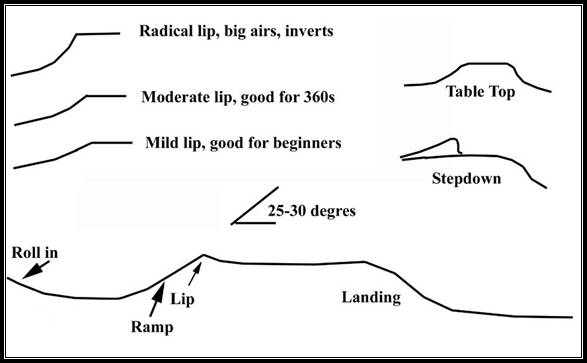

Jumps

Jumps come in a

variety of shapes but have many common attributes, as shown in Figure 9. Most jumps have a roll-in to build up speed

for the jump. The ramp guides the rider up to the lip, which has a major affect

on the type of trick performed. The ramp

angle varies from 25 to 30 degrees, as does the landing area. A mild lip is

great for beginning park riders and helps them gain confidence without the

compression feel from more radical lips, which may be frightening early on. A

moderate lip is good for rotary moves such as 360’s and 540’s. The radical lip

is good for big air moves such as corks and flips.

Figure

9

The table top jump is

a common beginning jump, while the step down design is usually set up for the

intermediate and advanced freestyler. A step down makes

a more efficient use of snow, since it takes advantage of the slope of the

hill, yields more air and requires less snow than a table top.

Figure

10

Figure 10 is a view

of a nice grooming job on an intermediate step down jump, showing a smooth,

uniform approach ramp, culminating in a moderate lip that should yield some

nice air for rotary moves. The landing area is approximately the same down

angle as the takeoff angle. Taking your students over small rollers helps them gain

confidence for the further flight distance required in this jump. Check the lip

periodically to make sure your students can handle it. Meet with the park grooming staff with any

suggestions you may have as to improving the jump performance. Perhaps salting

the lip area (on warm days, above freezing) or occasional shaping will help it

retain shape longer during heavily used periods.

Flow through a

Your student’s

journey through the terrain park should be exciting, varied and interesting,

therefore, good flow. There is a diversity of opinion on what good flow is.

While learning a new move, a rider may be focused on one feature and may not be

interested in the relationship of the features to each other. This rider may be

hiking the feature, or may prefer a greater approach distance for setup. On the

other hand, a rider who is jibbing the park may be

interested in putting together a smoothly flowing run that uses multiple

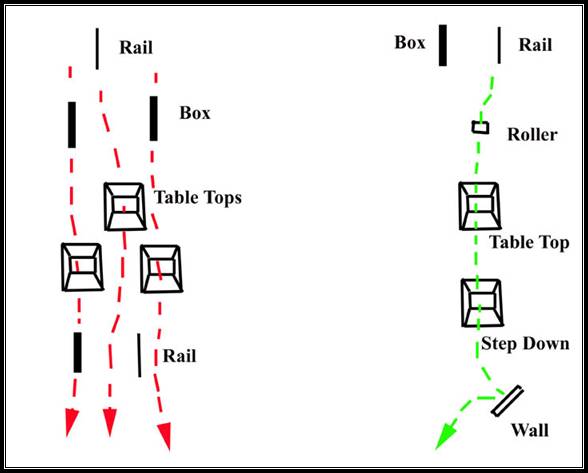

features. On the terrain park shown on the left in Figure 11, several runs are

required to hit most of the features. The park shown on the right has features

laid out such that the rider can hit many features in one run (jibbing), and

there is adequate preparation distance between features. The park to the right

has flow. Varying the location of features, or swapping out different features from

day to day, also makes jibbing the park more interesting

to your students.

Figure

11

Several aspects of

terrain park management and design have been discussed with emphasis on

assisting the park instructor on the ins and outs of what it takes to have a

great lesson in the park. Management may be looking to you for advice on what

riders like in the park and is interested in feedback from you on how your

students liked the experience. Park

layout is evolving rapidly with many new features and design ideas being

developed each season, so keeping up your knowledge base makes you a better

instructor and a more sought after employee of your snows sports area.

Chuck Roberts has taught alpine skiing since 1970 and snowboarding

since 1987. He is a PSIA-certified Level III alpine and AASI-certified Level II

snowboard instructor at